Theatre education in the penal system

In autumn 2021, a theatre education project took place in Affoltern am Albis (Kanton of Zurich, Switzerland) prison as part of a teaching module at the Zurich University of the Arts. Under the direction of two lecturers, a group of ten students worked for six weeks with people serving a prison sentence.

The innovative aspect of our approach from the field of performative theatre education is the creation of playful realities. Performativity in theatre means physical or linguistic actions that can and should lead to our realities being changed or at least questioned. Much of our world, our reality, has a norm stamp. Everything that does not fit into a norm makes us uncomfortable in some way and tends to be rejected.

Our theatre pedagogical approach is therefore to shift and distort realities, to provoke unusual ways of thinking, seeing and acting.

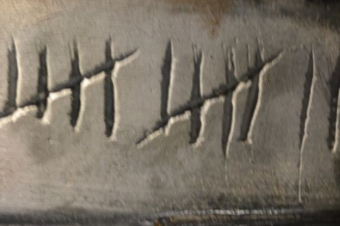

“Our first encounter with the participants of the Affoltern am Albis prison: We, the students, stand with the participants in a circle in the classroom and play “Brr-Tack”. In this game, one person makes a “Brrr” sound, holds his or her hands next to the ears and wags them to the sound until one then passes on with a Tack by means of an index finger pointing to another person. Over the next six weeks we were greeted from everywhere with “Brrrr” and the movement that goes with it. ”

This little game already changed a lot in a very routine, controlled and standardised everyday life. It led to a reality, in this case the greeting, being changed playfully and thus the meeting of people experiencing a slight shift to the familiar.

In the following time, different dialogue formats were developed on the topic of “What makes living together”. This discussion was about creating different kinds of encounters between people in prison and people outside, which would normally never be possible according to the rules of the penitentiary system.

Example 1: A telephone station was set up outside the prison where spectators could ask each other questions in a one-to-one situation with a person in prison.

Example 2: Another one-to-one telephone performance was: participants and the person from outside walked through their “home” together, like in a fictitious flat-sharing visit, described what their respective homes looked like, drank a glass of water “together”, etc.. A situation arose in which the commonalities and differences of the various living situations were experienced and discussed.

Example 3: Or an interactive, digital theatre game was produced, which took place in a reality TV format. The audience was connected live and could choose from different façade images during the performance and decide which façade they wanted to look behind.

But equally valuable were the small, brief moments in the rehearsal phase when shifts in reality were achieved. For example, during a filmed scene in which a participant was changing a baby doll and six other participants were watching touchingly. The participant took the doll back to the cell that evening, as he wanted to make another dress for it, but a guard found it and confiscated it. A central rule of the prison: the doll could be turned into a smuggled object by the inmates.

Once again, these realities collided unchecked: the doll as an object to which beautiful emotions and memories of being a father are attached and the doll as an object that makes the participant into an inmate again and thus reinscribes him in the norm.

Educational work in prisons as performative theatre pedagogical work questions given conditions and, for example, as in the case of our performance formats, brings people from inside and outside into joint thinking, speaking and acting. Together they playfully work on social transformation, criticise and create something new. Instead of “only” making the inmates capable of integrating into the existing social norms, many of which are unjust.

Outlook: For us theatre educators, this work is socially relevant. For this reason, we will work towards realising other similar theatre education projects in prisons. In a next step, we will try to establish a longer-term theatre education programme in a prison that allows inmates and staff to develop playful realities of living together.

We would be very happy to exchange ideas with professionals from the field of education in the penal system!

Contact: markus.gerber@zhdk.ch